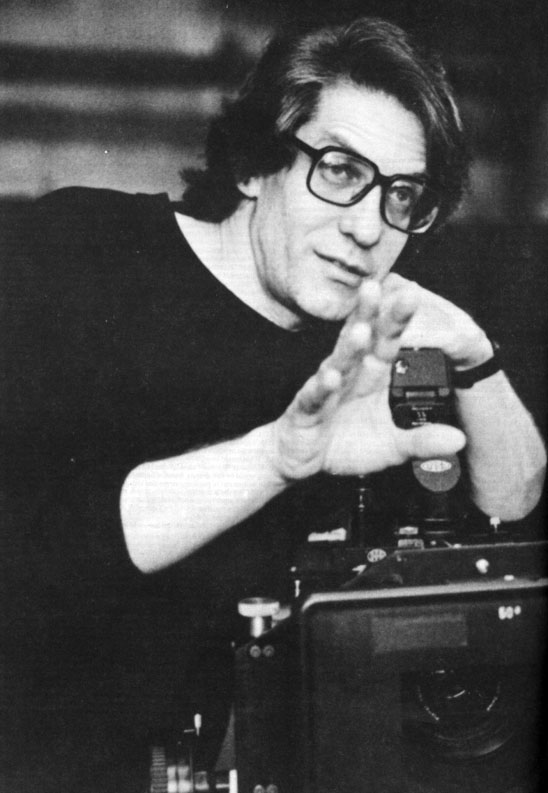

Zum Kinostart von David Cronenbergs «The Fly» (1986) hat Michel Bodmer, heute stellvertretender Leiter des Filmpodiums Zürich und damals Journalist beim Filmbulletin, gemeinsam mit seiner Kollegin Christa Telles (Szene) den kanadischen Regisseur in Hamburg interviewt. Das vollständige Transkript des Gesprächs können Sie nun auf dem Blog des Filmpodiums nachlesen, anlässlich der Aufführungen von «The Fly» als Teil der Programmreihe «Das erste Jahrhundert des Films: 1986». Im Interview spricht Cronenberg über seinen Bezug zum Genre des Horrorfilms, seiner romantischen Ader, den Unterschied zwischen Fantasie und Furcht und der Möglichkeit eines Sequels (es gibt tatsächlich ein Sequel von Cronenbergs erfolgreichstem Film aus dem Jahre 1989 – The Fly II. Gemäss dem Regisseur wurden seine eigenen Pläne für eine Überarbeitung des Films, an denen er seit 2011 gearbeitet hat, nie verwirklicht).

Christa Telles (CT): The Fly is your most successful film to date.

David Cronenberg (DC): Yes, by far.

CT: Did you expect that, or did that come as a surprise to you?

DC: I always think that what I’m doing is going to be successful. I’m surprised when it’s not. When it’s a success, I say, ah, yes, that’s normal, that’s the way it should be. I’ve had some films that have had some success, but not like The Fly. When I’m doing it, I’m very excited about it, very enthusiastic, and I think it’s wonderful, naturally, and I therefore think, it’s going to be a success. Even though I know, rationally, that there are many reasons why it doesn’t work. So I can’t say I was surprised, really.

CT: The Fly contains most of your main themes, and one explanation for the success could be that horror is one of the most popular themes at the moment…

DC: I disagree. Fifteen years ago, people were saying the same thing, and when you think of it, there’s almost no year that goes by in which there hasn’t been at least one very, very successful horror film. I mean, Rosemary’s Baby was in 1969, The Exorcist was in ’73, and The Omen and even Friday the 13th were successes, even though they were very low-budget. And when you think about it, horror has in fact been incredibly consistent.

CT: But there is a new kind of horror, which is combined with humor…

DC: If you’re talking about The Fly specifically, yes. There are a lot of things that I put together in The Fly that I hadn’t put into one film before. It’s very romantic, first of all. It’s really a love story, and it’s very obsessive, and it’s very sexual, and it’s also very funny. I have done all those things before in some movies, but I’ve never had them all work in one thing. Still, that doesn’t guarantee success. It’s maybe banal to say this, but it’s true: One of the reasons is that 20th Century Fox have done a very good job distributing it. That’s incredibly important. I think that Dead Zone could have been much more successful in the theatres in America and in Europe, if it had been well distributed. I was very disappointed in Paramount, who have a very good reputation. It might not have made 100’000’000 $, but it could have made three or four times what it did. From a practical point of view – critically that’s not very interesting – people have to know about the film in order to have access to it, before it becomes a success. That’s the first thing.

Michel Bodmer (MB): Do you find that you are constrained in your work by working with big budgets and big studios?

DC: No, it’s only been good. The budget of The Fly was 10’000’000 $, which was certainly the biggest budget I ever had, but in Hollywood… They were excited to have the film look as good as it did and be that cheap. They were really happy. So there were really no constraints. The good part was that you have the machinery of Fox – publicity and distribution – pushing the film and making sure that people go to see it. It’s only been good so far.

MB: You haven’t had any kind of artistic interference?

DC: No. And it’s interesting about The Fly: If you think about it, the horror genre really protects me; if I had gone to a major studio and said, «I want to do a story about two people who meet and fall in love, and then one of them gets very sick and slowly and horribly dies and has to be killed by his lover, and that’s the end of the movie», they would have said, «You’re crazy». But no-one ever questioned that aspect of the film. Because it’s a horror film, they accepted that it could be extreme and not have a happy ending and so on. I might have had some kind of artistic interference, if it had been some kind of naturalistic drama; I don’t think I would have ever gotten it made, but now I had no trouble.

MB: The word «cancer» occurs in the film – so that was one of the elements you were aiming at. On the other hand, in the early stages of Brundle’s transformation you have this obsession with the concept of «the flesh», of an evolutionary step forward. This is something new, that you introduced, which was not in the original material?

DC: Yes.

MB: It’s interesting, by the way, that German doesn’t have an equivalent for the word «flesh»…

DC: Really?

MB: There is no word for «animate matter»…

DC: Only «meat»?

MB: Yes. It strikes me that you often deal with this interface between mind and body and the mutual effect the two can have on each other. Is this something that you want to pursue even further, or do you think you’ve covered all the angles by now?

DC: No, I don’t think I’ve covered all the angles, I think there are a few more… Because it’s such a basic angle. It’s a very big mystery, and it involves so much. It does involve sexuality and love, and it does involve death and mortality; these are very heavy subjects, and nobody has covered all those angles, and I don’t expect to be the one to do it. So it’s my own particular approach to what I think is a very standard subject of art – death and love and sex – that’s pretty basic stuff.

MB: You’ve made a number of films that deal with the limits of mind and body and the interplay between them. Most of them are labelled horror films and are, in fact, pretty revolting in parts. You’ve said elsewhere that it was your «fantasies» rather than your fears that were being acted out on screen. Where do you draw the borderline between fantasy and fear?

DC: A fantasy can also be a fearful fantasy. That’s a matter of semantics. When you say, «That’s my fantasy», some people assume that you mean something you would like to actually have happened. I don’t think of it quite like that. I think you can have a fantasy of something horrible, that you hope will not happen. When I say fantasy, I mean [Brundle] is transforming. The Fly is a story about a man who transforms. But I think we are all transforming, right at this instant. You are, and I am. We started as something else, and we’re growing, we peak, and we grow old, and our teeth do fall out, maybe, and maybe our ears don’t fall off (but maybe they do), our hair falls out… We will transform. We are in the process, we just don’t see it. So if you think of The Fly as a 40-year love affair compressed into three weeks, and think of him as aging – not as having cancer or AIDS or whatever – and having to deal with it, having to look at himself and trying to find something positive and something good – that’s a fantasy. I don’t mean that it’s something I want to happen. I think it is happening; to me, and to you.

MB: I was referring more to something like Shivers, where you said that, for you, the ending was a happy ending.

DC: Yes. Because it’s a fantasy of liberation beyond what I think is actually possible in human beings. It’s like when T.S. Eliot talks about wanting to be a lobster; he means, to be free of the incredibly complex social structure of guilt and responsibility and everything else that human beings have. I mean, if you’re a lobster, you have no responsibilities. You just do what a lobster does. You exist. When you are driving yourself mad with all of these things, it’s a kind of a fantasy to think that you could just become sexual, nothing else, with no social aspects to you… People try to do that, people drink to do that, to reduce themselves to some basics. That’s really what I mean. I don’t mean that I wish it were happening.

CT: There is a lot of the «Beauty and the Beast» theme in The Fly. That’s a theme of love. In most of your films I missed a real value, the value of love of something ideological. I was surprised, when I saw The Fly, that there is this love, this value.

DC: I am basically a romantic. Really. (She doesn’t believe me.) Part of what I’m doing is a search for value. That’s what a lot of my films are about. And it’s accepted. I don’t consider myself a philosopher/moralist who knows what we must do and therefore my films will tell you what to do. In fact, it’s the reverse. I don’t know what to do. And what I’m showing you in my films is me stumbling around, trying to find what might work. That’s really the way it feels to me.

CT: One of the most important lines in Videodrome, to me, was that Videodrome is dangerous «because it has a philosophy». I think you are looking for a philosophy. You don’t have any messages, you’re looking around. Is philosophy really dangerous?

DC: What the woman in the film meant by that line was that someone who is that focused and that directed is a dangerous enemy. If we think of the Soviet Union as an enemy, the more righteous and the more focused in believing that what they’re doing is right they are, then the more dangerous an enemy they are. That’s one of the aspects: I think it can be dangerous to have a philosophy that you give yourself to, under any circumstances, that you develop a philosophy, and no matter what reality tells you, you will not change it and react only in terms of that philosophy. I think that is dangerous. There is a danger in having a philosophy, when it becomes a code of behavior, and freedom of choice and observation are ruled out. Then, philosophy is dangerous. It is an important statement in the film, and reflective of a lot of things in me. Even though in most of my films I don’t have a body of philosophy and say, «This worked for me, you should try it», I do have many observations, however, that I make, that I believe to be true, that I don’t think a lot of people have made about their own lives. So that’s not exactly a moral philosophy or a political philosophy; it’s something from which, maybe, that could be developed.

MB: To pick up on the notion of ideology and philosophy: Some people have accused you of sexism; Robin Wood has accused you of being reactionary, and that strikes me as odd, because what you’ve said about breaking down limits, developing and evolving, seems to me, if anything, progressive or even subversive…

DC: If Robin Wood believed that I was subversive, he would say nicer things about my movies…

MB: There are different kinds of subversiveness…

DC: Yes. But here’s a perfect example of the danger of philosophy. Robin Wood is a very bright man, I know him reasonably well, and we’ve had many amusing debates. But at a certain point in his life, he realized he was a homosexual, he left his wife and children and devoted his whole life, I think – in what is undoubtedly a very superficial Freudian analysis of another man’s life – I think, he has made his whole life different, to justify what he has done with his life. I don’t think he has to justify it; I think he feels he has to justify it. He was a well-known critic before this happened; he’s written a book on Bergman, and on Hitchcock that are quite well known. He’s now very Marxist-Leninist, gay, feminist – he has a T-shirt that has all these things on it together – and Freudian. And he has a very rigid critical philosophy now, which forces him – and I’m not necessarily talking about my own films – to promote as wonderful filmmakers that he knows are terrible, because they’re politically correct – Soviet socialist realism or something, at least, his strange version of it – and to abandon or criticize filmmakers which he finds fascinating. He’s intrigued by my work, but he can’t say that it’s good, because he feels that it supports the patriarchal, capitalist, male-dominated – whatever it is that he feels he has become, he feels that I support the opposite.

MB: I don’t think that’s even true.

DC: No, I don’t either. This is what I find very strange. For some reason he has his mind set on this and believes that to be true. It’s true, for example, that in The Brood, there’s this man whose marriage breaks up, and there’s the destruction of the nuclear, paternalist family, in Robin’s terms. There is a sort of pain involved, for the main character, in that the classical family unit has broken down. And so I think he thinks that because I allow my characters to have pain at the destruction of something that they’ve built, that it means that I’m supporting it, and that I find any alternative lifestyle repulsive. Well, that’s a huge jump. This is what I mean about a philosophy being dangerous. It’s almost as though he feels that if you happen to be happy with the heterosexual family relationship with a couple of kids and a wife, that this is a political atrocity and a betrayal of humanity and everything else. And that’s what I don’t like about a philosophy, when it becomes a sort of rigid moral code that you must obey or you’re a bad guy. And that’s, I think, what he is saying. I don’t believe that by saying that I think you can have a nuclear family that works well, I’m criticizing him for living with his male lover. I’m not. I mean, that’s fine, that’s okay. So he sees it as a threat to the revelation of his own life. It’s very complicated, this stuff, these critical relationships…

MB: Another thing that strikes me is that it’s very often quite difficult to actually sit there and watch the films that you’ve made, because some of them are really very, very gross and horrid. And I was thinking, obviously there’s a lot more to them than to a simple splatter movie…

DC: Yes…

MB: Now, I find myself worried that the people who would appreciate the different levels, the complexity of your films might be grossed out by the surface. Do you feel that you have to pour it on that much to express something specific, or are you just fascinated by those effects, crying for «More blood!» and all that…?

DC: No, I’m not fascinated by the effects at all. Effects are totally boring. That’s the most boring kind of shooting in the world. The most fun you have is when you’re doing a dramatic scene with actors; that is entertaining. When you have to go away for five hours and come back and do one shot, and it doesn’t work and you go away for another five hours – that is really boring. So I’ve long lost my fascination with blowing things up and breaking things open. I mean, I’ve done that, and now it’s just part of making a movie. But it’s interesting that you talk about people being put off by the surface. An interesting phrase, because, you see, what they’re really put off by is the inside…

MB: … coming out…

DC: Yes. I think it’s an essential part of what I’m doing. Even though I agree with you that it’s possible that it puts off people who otherwise would really like the films and who I would like to have as an audience. To me, it’s a measure of my integrity that I continue. I haven’t run into this lately, but in the old days, there were people who would say, «You’re doing this gore just to make money». And I think, absolutely, that The Fly might have been even more successful, if I had pulled back a bit on that stuff. But that’s one of the things that I’m discussing. Because I’m talking about love and death and aging and mortality, and for me that’s extremely physical. Very physical. There are many mysteries and paradoxes about our relationships to our own body, which leads us to paradoxes in our relationship to our own mortality. It’s very strange to me, for example, that if you were to open your own body and look inside, you would be repulsed. Don’t you think that’s strange? I mean, it’s you. You walk around with it, you live with it, it’s absolutely you. And yet, you don’t have an aesthetic that can deal with that. People think of a woman as being beautiful, but really it’s the surface. Inside of that woman, which is a part of what she is – if you were to think of a woman that was totally beautiful, I would think that you would think she had a beautiful spleen or kidney. I don’t mean that you’re cutting her open, I’m not talking about that, but that you would really have a total appreciation of her, physically. Because after all, when we talk about beauty, we are talking about physical beauty, to begin with. This, to me, is a great paradox, and I think it means that we have not yet fully come to terms with what we are. So I’m discussing that in the film. As a child I loved insects and was fascinated by animals and all that kind of stuff. Most people would also find a documentary on insects disgusting. You see them on TV, and you see insects laying eggs, and the larvae grow out, and people are just revulsed by that. But it’s absolutely natural. It’s nature. It’s happening right out there, in the lake, in the trees, right now. Well, they’re quiet now, it’s cold… And it’s just business as usual. And we can’t deal with it. And it’s part of the physical world that we live in, that we’re fascinated by, that we continually try to change. If you think of this movie, The Fly, as a nature film, as a film about this creature, which shows how he develops, and how he mates, some people would still be repulsed and some wouldn’t. So I’m deliberately challenging your sense of aesthetics, and I realize that some people don’t want to have it challenged that way, but I do think it’s an integral part of what I’m doing. I mean, it’s not the same as showing people being shot on screen. I don’t think, for example, that I could do that off screen and have you know what I meant. I think that what I’m doing on screen is something that you couldn’t imagine on your own. Therefore I couldn’t do it off screen and just have sound effects and you would know what was going on. Even in Scanners, where this fellow’s head blows up: if you imagine that I did that off screen, and you heard a bang, who would have thought that this guy’s head had blown up? Cinematically, technically, I did not know how to tell that without showing it. That’s really my approach to those things.

CT: Is PSI the key to psychological beauty? In two of your films you had PSI. You showed people in their inner beauty, the inside that is important; they have a body, they have flesh, they have everything a human being needs, but I think the beauty is inside of them. You talked about physical beauty, that everything inside is connected with the outer surface…

DC: But it is. I’m beginning with that. I’m talking about physical beauty, I’m not saying that there is no other kind. But when we talk about spirituality, say, you talk about the art of the Middle Ages, which discusses, in particular, spirituality and mortality: It is full of twisted, horrible, mutilated figures of the various saints and Christ and everything else, there is no way that you can have spirituality or mentality without body. They’re fused forever. They’re not the same, but they need each other. It’s like a symbiotic relationship between two creatures, mind and body. And that relationship and the paradox of that is also very much what I discuss. And you don’t have beauty without having a mind that perceives beauty. I don’t think an insect has a concept of beauty, even when it sees another insect that it really likes… I don’t think it’s the same as when we see someone who we think is beautiful. I’m absolutely not saying that it’s only physical. Not at all. But it is also physical. Any attempts that we have to divorce the two are always laughably pathetic, I think. It never works. And if you talk about moral values: In all my films I’m discussing this stuff. I’m trying to figure out what to do with it myself.

CT: Are you connected with the «New Age» movement?

DC: I’ve never heard of it. What is it?

CT: It´s ‹back to basic living›, etc. In Dead Zone the doctor tells the telepath, «You have either a very old or a very new ability of human beings», and I thought that was very «New Age»…

DC: Well, of course, the doctor could be wrong… The truth about my relationship to my characters, and I’m certainly not unique in this, is that it is a very complex one, because I have characters who say absolutely opposite things, and I don’t always personally believe what my characters are saying. When I write it for them, I’m believing it, so I can understand it. In Videodrome I have some men making some very strong statements about many things, which I absolutely do not believe. But for the moment that they say it, I believe it. So the doctor could well be wrong. I don’t believe in telepathy.

CT: In The Fly you play a doctor. Why? Because you’re so interested in the human body…?

DC: To tell you the truth, it was because I have a mask on, and if I didn’t do a good job, I could cut someone else’s voice in very easily… I was casting my producer, Stuart Cornfeld, to play the doctor. And just before we started to shoot, he didn’t want to do it. He was afraid. Not because it was gross, but because he felt he would hurt the picture. He didn’t think he could do it properly. He had acted in one or two movies, but always comedies, and he was really worried that he would not be right. We didn’t have an actor. That was my excuse.

MB: Coming back to this attitude that you said we have to our bodies, and that a lot of the stuff that seems gross to us seems natural to you: in another interview you said that you once went to see Shivers, and someone had brought their three-year-old daughter to see the film, and that you were upset by that. Do you try to bring up your own children so this will not be gross to them, that they have a different attitude to their bodies?

DC: I would, if I knew how to do it. But I don’t really know how. The most I can do is a very simple thing: My son loves insects, he’s very interested in them, for example. Now, children automatically pick up things from their parents, including their fears and prejudices. If you’re brought up by parents who are terrified of spiders or go crazy when they see a fly, then, as a child, you assume that attitude, and it takes quite a lot to reverse that. And my son will pick up a spider and let it run on his hands, while some people go crazy. That’s really the most that I think I would want to do: to let him know what my attitudes to those things are, and then he develops his own. If I could do what you suggested, I’d do it. But I don’t know how to do it myself, so I have no idea how to do that for my children. And I can’t really see myself starting a school to teach these things, but the most I can do is make these movies.

MB: You’ve made two films now [Dead Zone, and The Fly] which are not based on your own original material. Was that a conscious decision?

DC: No. In fact, if you’d asked me about it some time ago, I would have said, I’d rather not do it. But now that I’m more mature about it, I’m not worried. You can work yourself into a frenzy or paranoia about what is really yours and what is not yours. I think I’ve come to the realization over the years that I have an instinctive kind of feel for what I should do or not do in a film, and what kind of film. I’m not saying I could never make a mistake. Everybody seems to make a mistake one or a few times that way. I just let my instinct guide me. I did think, when they said, «We’re going to send you this script; it’s a remake of The Fly», I’d say, «Don’t bother, I’m not the slightest bit interested in doing something like that. I’m not interested in doing a remake, and I’m not interested in particular in doing a remake of The Fly.» But instead I said, «Well, okay, I’ll look at it.» And when I read it, I knew, right away, that I wanted to do it. It needed to be changed, but I knew there was something in it, really the idea of a transformation, which I immediately felt had some metaphorical force, for me. So I immediately stopped worrying about whether it was mine or not. In fact, I was happy to share the writing credits with this guy [Charles Edward Pogue], because he did write part of it.

MB: I was surprised to see you do Dead Zone, because I think your kind of horror is quite different from Stephen King’s…

DC: Yes, I agree.

MB: Yours is far more disturbing to me; I find King rather overrated. But you seem to have streamlined the book to those things that could be of interest to your approach.

DC: I feel that aside from the fact that Stephen and I deal with the same basic material, that is to say, death, and fear, and so on, we don’t have a close kinship in what we do, and so I was really also surprised, myself. I was first asked to do Dead Zone about three years before I actually did it. I read the book. For various reasons the rights were lost or something. Three years later I was again approached, and I immediately said yes. And that surprised me. Once again it was my instinct telling me what to do. I was surprised that I would do Stephen King, and in particular that book. What I think happened was, that it had sort of settled and I really could relate to a lot of it. And it was sort of another angle to some of my own material.

CT: Most of your films are about changes; people seem to lead a normal life, and something happens, something changes. Is it your opinion that the changes come from inside? Is there no way to change people by means of their surrounding, etc.?

DC: I’m not saying that other changes are not possible. I’m just saying that the changes that interest me the most are the ones that come from inside. I wouldn’t rule out making a film about it happening the other way, but that’s just what fascinates me the most, because most people don’t think that they change. Most people don’t realize how much in fact they do change. When I say that while we are sitting here, we are transforming. It surprises me to think of that as well, but it’s true. So maybe because it’s less obvious and less frequently explored, that’s why I’m more interested to do it. I don’t mean to say that we are fated, that there aren’t other ways for us to change. In fact Dead Zone is sort of a politically overt film; it’s really talking about actually changing the future by actual personal action, and I believe that. That’s very possible.

CT: A stupid question: Is there going to be Son of the Fly soon, or Daughter of the Fly?

DC: It’s not so stupid. It won’t be coming from me, but Fox are interested in doing a sequel.

MB: With the unborn baby or what?

DC: Yes. You see, in my opinion, she would never have that baby. And when they talked to me about it, I said, «Look, if I do a sequel, I would like it to be so different: I would maybe do a film about teleportation and the implications of that», because that’s actually a very interesting subject which I had to keep in the background of my film. And they said, «But then there would be no reason to call it The Fly.» So I think they are talking at the moment about a film in which she does have the baby, and if I were involved, it would just be as a godfather; I’d give my blessing… But if I were to do it, I would insist that it be understood that she would not have that baby. Because I don’t think, psychologically, there is one woman in the world who would have that baby. I wouldn’t…

Hamburg, 20. November 1986

Und wer noch mehr lesen mag: Ein spannender Hintergrundartikel in der TagesWoche über «The Fly» – ein Film, der auch 30 Jahre nach seinem Startdatum nichts an Aktualität eingebüsst hat.